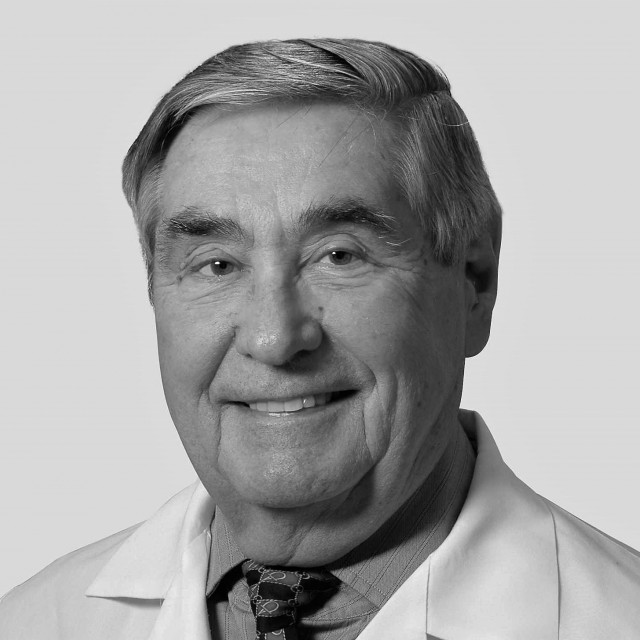

- Dr. Javad Hekmat-panah

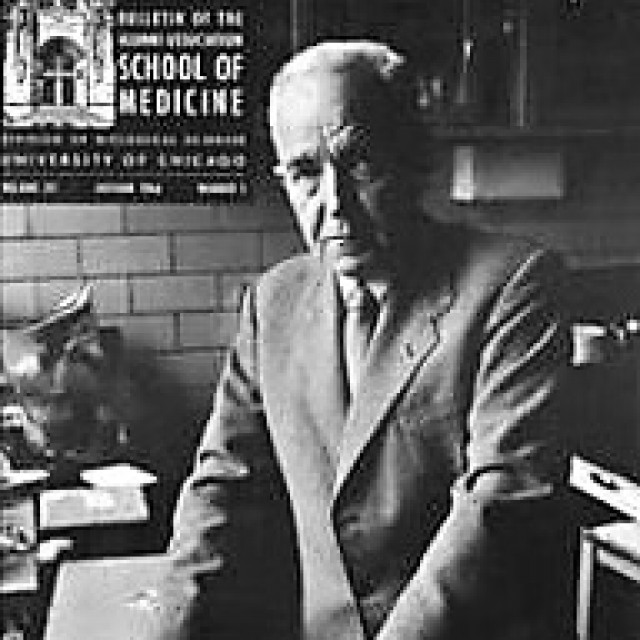

I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Bailey only on a few occasions when he was retired and when I was in my early neurosurgery training. On one occasion, Dr. Edward Tarlov, then a medical student, invited him to give us a talk. Dr. Bailey talked about the history of neurosurgery and his relationship with Dr. Cushing, in which, while he expressed his appreciation in having been trained by Dr. Cushing, he could not hide his true feelings. What stands out in my mind is his comment about Dr. Cushing once insulting his resident, Dr. Dandy, during an operation where Dr. Dandy had cut the sutures with his left hand and was told by Dr. Cushing to cut them with his right hand, stating “you are clumsy enough” with that. Dr. Bailey believed that it was unfair, for he believed that Dr. Dandy was in fact more dexterous than Dr. Cushing.

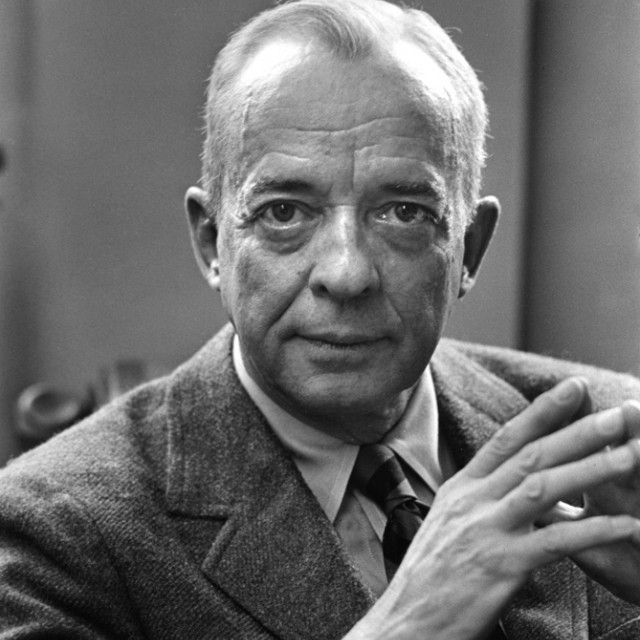

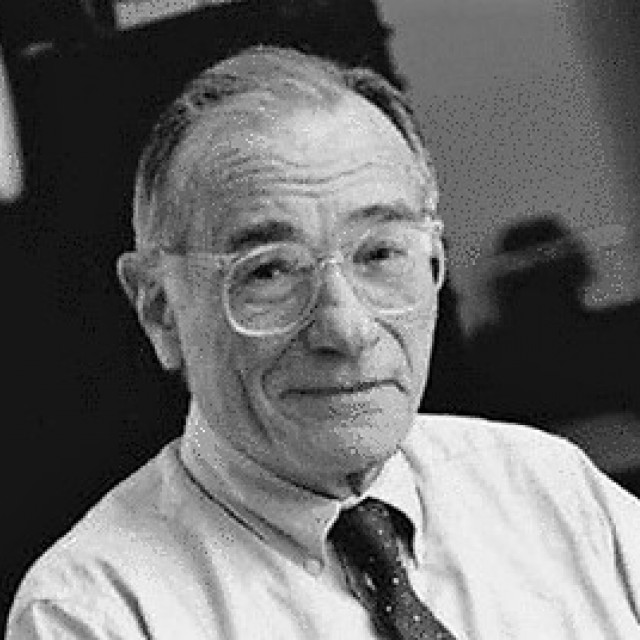

I started my neurosurgery training at the University Chicago in July 1961, having had over a year and a half of psychiatry training in Iran and three years of neurology at the University of Wisconsin. My mentors in neurosurgery were Dr. Joseph P. Evans and Dr. Sean Mullan, to whom I remain grateful. Dr. Evans was an excellent neurosurgeon and an outstanding diagnostician; his research interest was in head injury. He was a humanist. A lawyer even once told me that he believed that Dr. Evans was one of the most honest doctors he knew in Chicago. Dr. Evans was the chairman of neurosurgery from 1954 to 1967, when Dr. Mullan became the chairman. Dr. Mullan was an outstanding neurosurgeon with excellent technical ability and with unconditional dedication to care of his patients. His interest was innovation, improvement, and finding new treatments.